Three Refuge Cities – Deuteronomy 4:41-49 – Part I

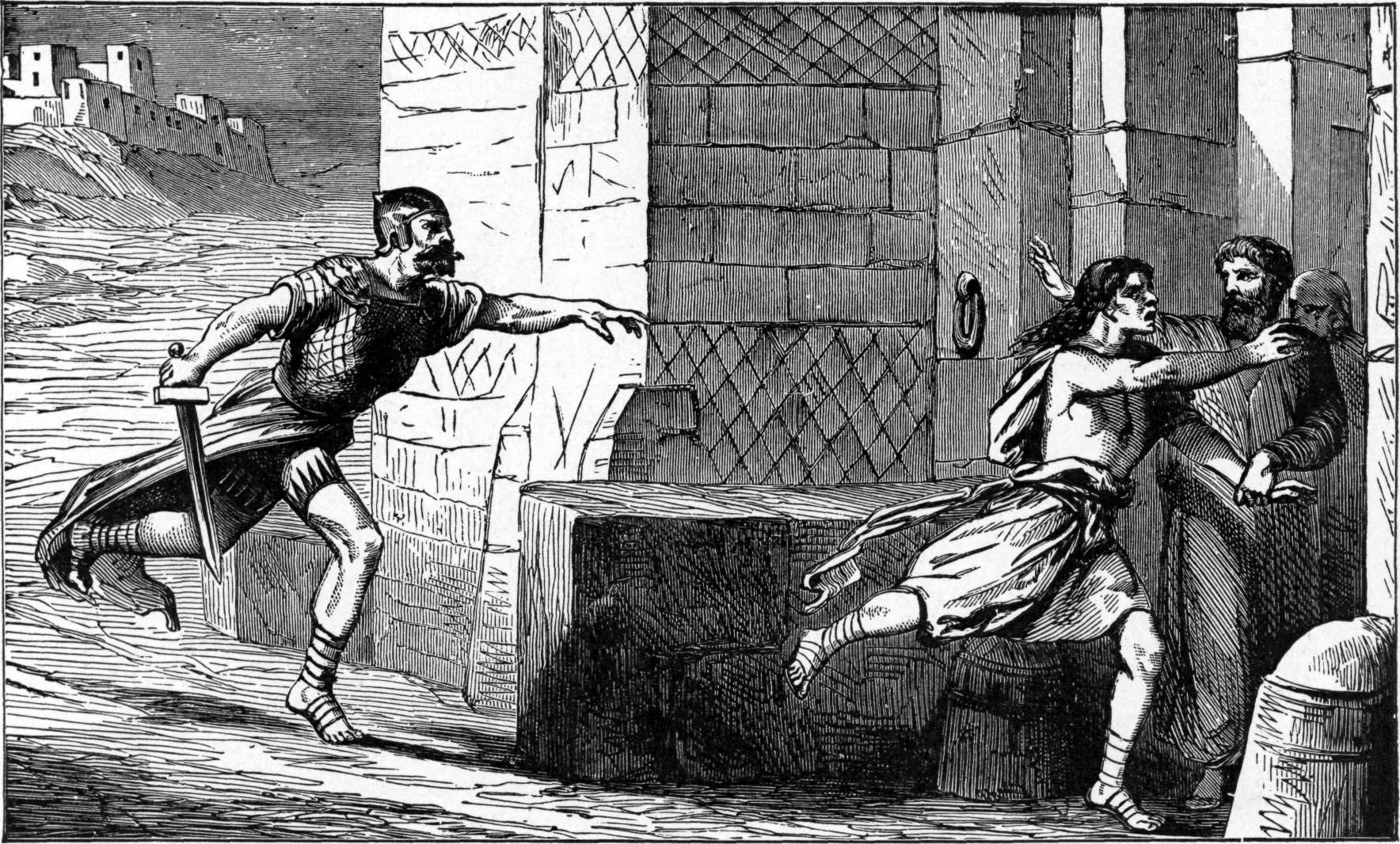

Torah Judaism is not far from Judaism’s tribal roots and Deuteronomy 4:41-49 shows this up quite clearly. This verse talks about three refuge towns on the east side of the Jordan River, Bezer (for the Reuven tribe), Ramot (for Gad) and Golan (for Menashe), to which someone who accidentally takes the life of another can run in order to be safe.

Illustrators of the 1897 Bible Pictures and What They Teach Us by Charles Foster [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

- A person’s interactions with others; and

- A person’s interactions with himself or herself.

Refuge Cities and Interpersonal Interactions:

The price for taking a person’s life is his or her own life. Naturally, emotions run high after someone is killed and vengeance by lynching may have been common. We saw how that happens even today when the unfortunate Haftom Zarhum was beset by an angry crowd in Beersheva in mid-October this year after he had been downed as a terror suspect.

Israel mob lynch Eritrean immigrant after bus station attack https://t.co/BGRBP5eRg6

— MobileAfrican.Com (@NigellaRauben) October 26, 2015

The Mosaic Laws do not seek to change human nature but to moderate it. As one measure, the Torah speaks of “go’el ha’dam” (גואל הדם), meaning that only a blood relative of the victim can exact the punishment for murder. This clear restriction regarding who can carry out the death penalty seems necessary in order to put a hold on the natural human impulse for revenge that can cause crowds to run amok.

While it was accepted practice, then, for a family member of a murdered person to kill the murderer, they were not supposed to take out the pain of their loss on the killer if the killing was unintentional, an accident. In consideration of the fact that angry and hurting people do not tend to have the patience required to evaluate the circumstances of a death, a way to protect the killer who may be guilty of negligence rather than murder, is to allow a place of refuge.

The killer could run to the closest refuge city (there were 6 in all) and explain the situation to the city elders who provided shelter until they could hold a trial and determine whether or not the individual was guilty of murder or if the death was accidental. If the latter, the killer remained in the city, protected from the revenge that possibly still pulsated in the veins of the victim’s family members.

The high value attached to this idea of protecting the unintentional killer can be seen in the instructions for building the road to the refuge city: it was to be wider than those leading to other cities. Moreover, the roadway had to be maintained properly so that passage was smooth and unimpeded.

The Refuge City Foreshadows our Modern Justice System

Such attention to the need to protect the unjustly accused foreshadowed, perhaps, our modern justice system whereby there should be a clear and unimpeded path to the courts, with numerous checks and balances to ensure that an innocent person can prove his or her innocence and no longer be threatened with unjustified vengeance of the victim’s family or community.

Character Assassination

One need not kill someone to inflict life-changing harm. Harsh words, repeating rumours, deceit and manipulation of others can kill reputations or the will to live. Such acts can be intentional or unintentional. If the former, then whatever punishment is meted out by the hurt party may be justified (if criminal court proceedings are not relevant); however, if the latter, then refuge is a good idea, time to let those involved consider the circumstances and verify whether or not the injurious behaviour was unintentional.

Refuge Cities Protect the Victim as Well as the Offender

Retribution when harm is unintentional may be “overkill” and may mean that the victim or those close to the victim commit an unjustified injury to an undeserving individual. Keeping in mind the concept of the refuge city may help us slow down our tendency to pass quick judgement on others. The accidental perpetrator is advised, therefore, to lay low and stay out of sight and out of mind long enough for the injured parties to have had time to cool off and prepare themselves to calmly assess the context of the offensive behaviours.

Those who hurt us unintentionally have the right to prove that to us before we decide how to respond. It may be possible to apply corrective justice rather than punitive measures, thereby achieving more optimal outcomes for the primary and secondary victims and the unintentional offender.

Remembering this may help us progress another step along the path from our more primitive and barbaric ways of life to the civilized and enlightened state we claim to long to reach.